Gaussian Beams - Week 2

Contents

1 Where We Are in the Sequence

Week 2 of 4: Instrumentation and Noise Characterization

Last week you calibrated your photodetector and learned the knife-edge technique for measuring beam size. This week you’ll learn Python-based data acquisition and—critically—characterize your measurement system’s noise floor. Your goal: make a quantitative, evidence-based decision about which gain setting to use for Week 4’s automated measurements.

Last week: Aligned optics, calibrated photodetector, introduced knife-edge technique

This week: Learn DAQ programming → Characterize measurement system noise → Choose optimal gain setting

Next week: Learn Gaussian beam theory → Set up motor controller → Take first automated measurement

2 Overview

The second week of the Gaussian Beams lab introduces you to Python for data acquisition and guides you through interfacing Python with the instrumentation and data acquisition systems used in this course. You will also learn about digital sampling theory and characterize your measurement system’s noise floor—a critical step for making informed measurement decisions in Week 4.

An important discovery awaits: The DAQ device that records your data has its own noise floor—and this is what actually limits your Week 4 measurements. Every instrument has limitations. Expert experimentalists characterize those limitations and design around them. This week, you’ll do exactly that.

This week’s lab is divided into two parts. In part 1 (Prelab), you will learn essential curve fitting techniques that you’ll use throughout this course. In part 2 (Lab), you will learn Python programming for data acquisition using a National Instruments DAQ device, the NI USB-6009. This multifunction USB powered device has 8 single-ended (4 differential) analog inputs (14-bit, 48 kS/s), 2 analog outputs (12-bit, 150 S/s), 12 digital I/O channels, and a 32-bit counter. You will then apply these DAQ skills to characterize your measurement system’s noise floor and make a quantitative decision about optimal gain settings.

2.1 What is Python?

Python is a versatile programming language widely used in scientific computing and data analysis. Many research labs use Python for instrument control, data acquisition, and analysis. Its advantages include:

- Free and open source

- Extensive scientific libraries (NumPy, SciPy, Matplotlib)

- Large community with excellent documentation

- Easy to learn and read

- Works on all major operating systems

You can use Python on the lab laptops where it is already installed. See the Python Resources page for installation instructions if you want to set it up on your own computer.

2.2 Learning Goals

After completing the prelab, you will be able to:

- Explain why we minimize the sum of squares to get the best fit.

- Carry out a least-squares minimization graphically.

- Plot residuals to visually inspect the goodness of a fit.

- Interpret the uncertainty in fit parameters from

scipy.optimize.curve_fit. - Compute \(\chi^2\) for a fit and use it to determine if a fit is “good”.

- Create plots with error bars using Matplotlib.

After completing the lab, you will be able to:

- Connect a USB DAQ device to a computer and confirm the analog inputs are working correctly.

- Write a Python script to read analog voltage measurements.

- Configure sample rate and number of samples for data acquisition.

- Explain Nyquist’s theorem and choose appropriate sample rates.

- Recognize aliasing and understand its causes.

- Measure the DAQ noise floor and compare to datasheet specifications.

- Identify which component (photodetector or DAQ) limits your measurement system’s noise.

- Calculate signal-to-noise ratio and explain why gain improves SNR despite a fixed DAQ noise floor.

- Select and justify an optimal gain setting based on quantitative analysis.

- Confront predictions with measurements and identify sources of discrepancies.

- Save acquired data to a CSV file.

3 Overview of Your Work

This week culminates in a decision: which gain setting will you use for Week 4’s automated beam profiling? This isn’t arbitrary—you’ll build the quantitative evidence to justify your choice.

Prelab: Develop curve-fitting skills you’ll use throughout this course. You’ll learn to minimize χ², interpret residuals, and assess goodness of fit. These skills are essential for extracting beam radii from your knife-edge data.

In Lab: You’ll work through a predict-measure-compare cycle for noise characterization:

- Learn DAQ fundamentals — Read voltages with Python, understand sampling theory, observe aliasing

- Discover that configuration matters — Measure DAQ noise with different settings and discover that instrument behavior depends on configuration

- Identify what limits your measurement — Predict whether the photodetector or DAQ dominates system noise, then measure to find out

- Make your decision — Select a gain setting for Week 4 with written justification based on your data

See the detailed deliverables checklist at the end of this guide.

4 Prelab

This week’s prelab builds on the uncertainty concepts you learned during Week 1’s lab (where you measured voltage fluctuations and calculated standard deviation). Now we move from estimating uncertainties in individual measurements to fitting data and propagating those uncertainties to derived quantities. This is a “user’s guide” to least-squares fitting and determining the goodness of your fits. At the end of the prelab you will be able to:

- Explain why we minimize the sum of squares to get the best fit.

- Carry out a least-squares minimization graphically.

- Plot residuals to visually inspect the goodness of a fit.

- Interpret the uncertainty in fit parameters.

- Compute \(\chi^2\) for a fit and use it to determine if a fit is “good”.

- Create plots with error bars using Matplotlib.

4.1 Useful readings

- Taylor, J. R. (1997). An Introduction to Error Analysis: The Study of Uncertainties in Physical Measurements (p. 327). University Science Books. This is the standard undergraduate text for measurement and uncertainty.

- Bevington, P. R., & Robinson, K. D. (2003). Data Reduction and Error Analysis for the Physical Sciences Third Edition (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. Great for advanced undergrad error analysis. Professional physicists use it too.

4.2 Why do we minimize the sum of squares?

Question: Why do we call it “least-squares” fitting?

Answer: Because the best fit is determined by minimizing the weighted sum of squares of the deviation between the data and the fit. Properly speaking this “sum of squares” is called “chi-squared” and is given by

\[\chi^2 = {\displaystyle \sum_{i=1}^{N}}\frac{1}{\sigma_i^2}(y_i-y(x_i,a,b,c, \ ... \ ))^2\text{,}\](1)

where there are where \(N\) data points, \((x_i,y_i )\), and the fit function is given by \(y(x_i,a,b,c, \ … \ )\) where \(a, b,\) etc. are the fit parameters.

Question: What assumptions are made for the method to be valid?

Answer: The two assumptions are:

- Gaussian distributed. The random fluctuations in each data point \(y_i\) are Gaussian distributed with standard deviation \(\sigma_i\).

- Uncorrelated. The random fluctuations in any one data point are uncorrelated with those in another data point.

Question: Why does minimizing the sum of squares give us the best fit?

Answer: Given the two above assumptions, the fit that minimizes the sum of squares is the most likely function to produce the observed data. This can be proven using a little calculus and probability. A more detailed explanation is found in Taylor’s Introduction to Error Analysis Sec. 5.5 “Justification of the Mean as Best Estimate” or Bevington and Robinson’s Data Reduction Sec. 4.1 “Method of Least-Squares”.

4.3 Minimizing \(\chi^2\) graphically

You will rarely minimize \(\chi^2\) graphically in a lab. However, this exercise will help you better understand what fitting routines actually do to find the best fit.

Download and plot this data set. It was generated by inserting a razor blade into path of a laser beam and measuring the photodetector voltage of the laser light. The \(x\) column is the micrometer (razor) position in meters and the \(y\) column is the photodetector voltage in volts.

import numpy as np import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # Load the data data = np.loadtxt('profile_data_without_errors.csv', delimiter=',', skiprows=1) x_data = data[:, 0] y_data = data[:, 1] # Plot the data plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6)) plt.scatter(x_data, y_data, label='Data') plt.xlabel('Position (m)') plt.ylabel('Voltage (V)') plt.legend() plt.show()Define the same fit function as:

\[y(x,a,b,c,w) = a \ Erf\left(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{w}(x-b)\right)+c\]

In Python, this can be written using

scipy.special.erf:from scipy.special import erf def beam_profile(x, amplitude, center, width, offset): """Error function model for knife-edge beam profile. Parameters: x: position (m) amplitude: half the voltage swing (V) center: beam center position (m) width: beam radius w (m) offset: vertical offset (V) """ return amplitude * erf(np.sqrt(2) * (x - center) / width) + offsetNote on terminology: The parameter \(w\) is the beam radius—specifically, the \(1/e^2\) radius where intensity drops to \(1/e^2\) of the peak value. This is not the beam diameter (which would be \(2w\)) or the FWHM. Gaussian beam parameters are discussed further in Week 3.

Reduce the fit to two free parameters. This step is only necessary because it is hard to visualize more than 3 dimensions. Assume \(a_{fit}=(V_{max}-V_{min})/2 = 1.4375\) and \(c_{fit} =(V_{max}+V_{min})/2 = 1.45195\). These were determined by averaging the first 6 data points to get \(V_{min}\) and the last 5 to get \(V_{max}\).

Use Equation 1 to write an expression for \(\chi^2\) in terms of your \(w\) and \(b\) parameters, and the \(x\) (position) data and \(y\) (voltage) data. Since you don’t have any estimate for the uncertainties \(\sigma_i\), assume they are all unity so \(\sigma_i=1\).

def chi_squared(width, center, x_data, y_data, amplitude_fixed, offset_fixed): """Calculate chi-squared for given parameters.""" y_fit = beam_profile(x_data, amplitude_fixed, center, width, offset_fixed) return np.sum((y_data - y_fit)**2)Before running any code, answer these prediction questions in your notebook:

- What shape do you expect the \(\chi^2\) contours to have? (Circular? Elliptical? Irregular?) Why?

- If the contours are elliptical, what would it mean if the ellipse is tilted (major axis not aligned with \(w\) or \(b\) axes)?

- Where in the \((w, b)\) plane should the minimum \(\chi^2\) occur—at the true beam size and position, or somewhere else?

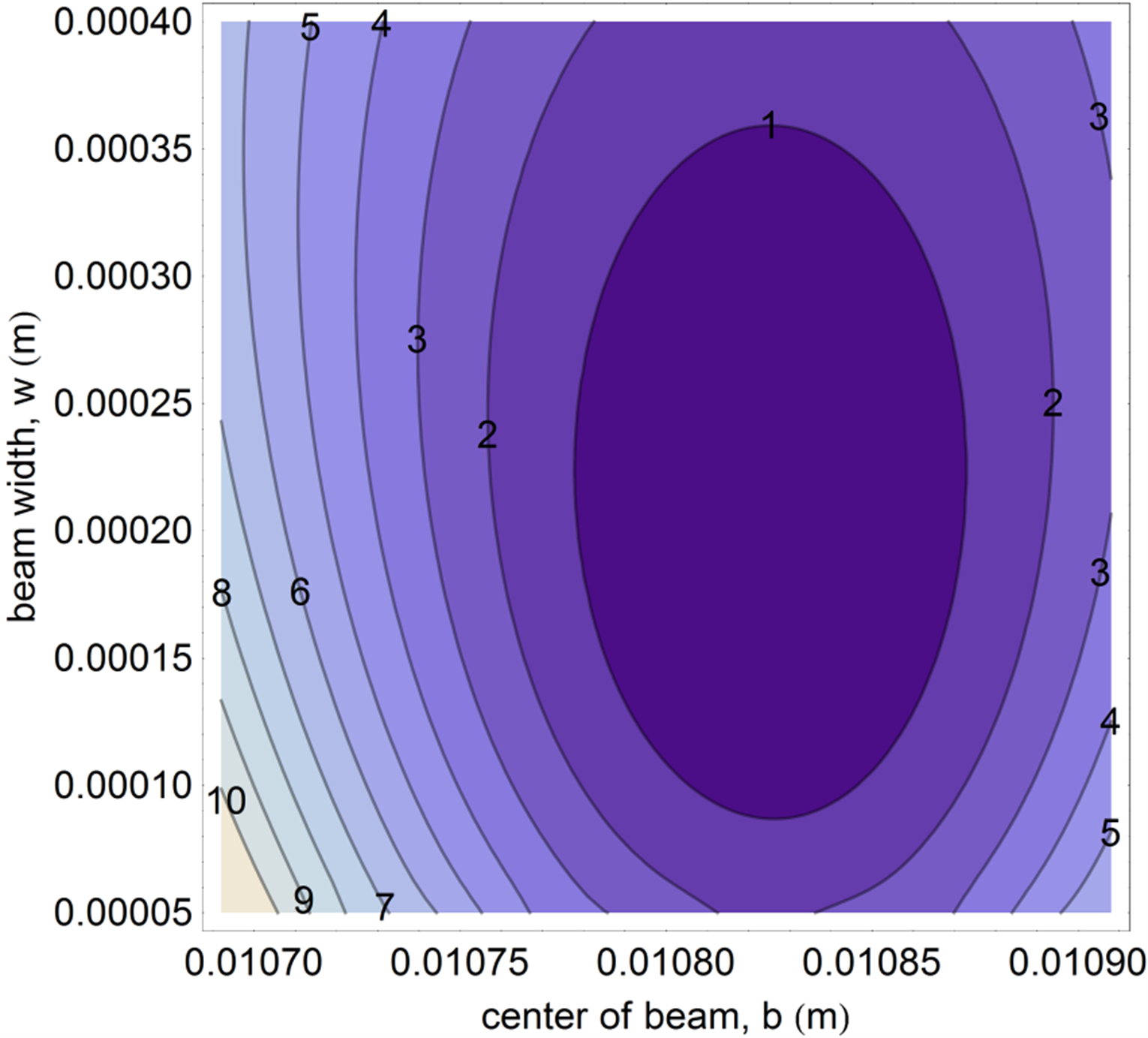

Make a contour plot of \(\chi^2(w,b)\) and tweak the plot range until you see the minimum (see Figure 1 for an example of what a well-tuned plot looks like). You can use AI assistance or the code below. The goal is to interpret the result, not to write the code from scratch.

# Create a grid of center and width values # NOTE: These ranges may need adjustment to clearly show the minimum! center_range = np.linspace(0.010, 0.012, 100) width_range = np.linspace(0.0001, 0.0006, 100) B, W = np.meshgrid(center_range, width_range) # Calculate chi-squared for each combination amplitude_fixed = 1.4375 offset_fixed = 1.45195 Z = np.zeros_like(B) for i in range(len(width_range)): for j in range(len(center_range)): Z[i, j] = chi_squared(width_range[i], center_range[j], x_data, y_data, amplitude_fixed, offset_fixed) # Make contour plot plt.figure(figsize=(10, 8)) plt.contour(B, W, Z, levels=20) plt.colorbar(label='$\\chi^2$') plt.xlabel('center of beam, $b$ (m)') plt.ylabel('beam radius, $w$ (m)') plt.title('$\\chi^2$ Contour Plot') plt.show()

Interpretation questions (answer in your notebook):

- Were your predictions from step 5 correct? If not, explain what you learned.

- The contours are likely elliptical and possibly tilted. Explain in 2-3 sentences why the parameters \(w\) and \(b\) might be correlated (i.e., why changing one affects the best value of the other).

- If the noise in the data were doubled, how would the contour plot change? Would the minimum move? Would the contours spread out or contract?

Graphically determine the best fit parameters to 3 significant digits. Record these values in your notebook—you will use them in step 9.

Checkpoint: Before proceeding, confirm you have recorded your graphical estimates:

- center \(b\) = _______ m

- width \(w\) = _______ m

Compare with the best fit result from

scipy.optimize.curve_fit(allow all 4 parameters to vary).Before running this code, examine the initial guesses below. Compare the center guess (0.01 m) to your data’s position range. What do you predict will happen when you run the fit?

Warning: You may get a

Nonlinear fitting algorithms likeRuntimeError!curve_fitare iterative—they start at your initial guess and search for a minimum. If your initial guess is far from the true minimum, the algorithm may:- Wander into regions where the function behaves badly

- Exceed its maximum number of iterations without converging

- Return a

RuntimeError: Optimal parameters not found: maxfev exceeded

This is expected behavior with poor initial guesses, not a bug in your code. Your \(\chi^2\) contour plot shows exactly why this happens: an initial guess outside the “valley” containing the minimum has no gradient pointing toward the solution.

If you encounter this error, proceed to the fix below using your graphically-determined values.

from scipy.optimize import curve_fit # Initial guesses: [amplitude, center, width, offset] # NOTE: These are placeholder values that may not work for your data! p0 = [1.4375, 0.01, 0.0005, 1.45195] # Perform the fit popt, pcov = curve_fit(beam_profile, x_data, y_data, p0=p0) print("Best fit parameters:") print(f" amplitude = {popt[0]:.6f}") print(f" center = {popt[1]:.6f}") print(f" width = {popt[2]:.6f}") print(f" offset = {popt[3]:.6f}")If the fit fails (RuntimeError) or produces unreasonable results: Replace the initial guesses with your graphically-determined values from step 8. This is standard practice—graphical exploration provides the physical insight needed to initialize numerical optimization.

# Use YOUR graphically-determined values as starting points p0 = [amplitude_fixed, your_center_estimate, your_width_estimate, offset_fixed] popt, pcov = curve_fit(beam_profile, x_data, y_data, p0=p0)After getting a successful fit: Do your graphical and computational results agree to 3 significant figures?

Reflection: Why did the original initial guesses fail (if they did)? Look at your \(\chi^2\) contour plot—where does the initial guess

center = 0.01fall relative to the valley containing the minimum?

4.4 Uncertainty in the fit parameters

Question: Where does the uncertainty in the fit parameters come from?

Answer: The optimal fit parameters depend on the data points \((x_i,y_i)\). The uncertainty, \(\sigma_i\), in the \(y_i\) means there is a propagated uncertainty in the calculation of the fit parameters. The error propagation calculation is explained in detail in the references, especially Bevington and Robinson.

Question: How does curve_fit

calculate the uncertainty in the fit parameters when no error

estimate for the \(\sigma_i\)

is provided?

Answer: When no uncertainties are provided,

curve_fit (and other fitting routines) estimate

the uncertainty in the data \(\sigma_y^2\) using the “residuals”

of the best fit:

\[\sigma_y^2 = \frac{1}{N-n}{\displaystyle \sum_{i=1}^{N}}(y_i-y(x_i,a_0,b_0,c_0, \ ... \ ))^2\text{,}\quad\quad\](2)

where there are \(N\) data points \(y_i\) and the best fit value at each point is given by \(y\), which depends on \(x_i\) and the \(n\) best fit parameters \(a_0,b_0,c_0, \ ... \ \). It is very similar to how you would estimate the standard deviation of a repeated measurement, which for comparison’s sake is given by:

\[\sigma_y^2 = \frac{1}{N-n}{\displaystyle \sum_{i=1}^{N}}(y_i-\overline{y})^2\text{.}\](3)

The parameter uncertainties are then extracted from the covariance matrix:

# Get parameter uncertainties from the covariance matrix

perr = np.sqrt(np.diag(pcov))

print("Parameter uncertainties:")

print(f" σ_amplitude = {perr[0]:.6f}")

print(f" σ_center = {perr[1]:.6f}")

print(f" σ_width = {perr[2]:.6f}")

print(f" σ_offset = {perr[3]:.6f}")4.5 Estimating the uncertainty in the data

Use Equation 2 and your best fit parameters to estimate \(\sigma_y^2\), the statistical error of each data point given by your data.

# Calculate residuals y_fit = beam_profile(x_data, *popt) residuals = y_data - y_fit # Estimate variance (N data points, n=4 parameters) N = len(y_data) n = 4 sigma_y_squared = np.sum(residuals**2) / (N - n) sigma_y = np.sqrt(sigma_y_squared) print(f"Estimated σ_y = {sigma_y:.6f} V")Compare your result with the estimate from the fit. The estimated variance can be calculated from the residuals.

Do the estimates agree? Why or why not?

4.6 Goodness of fit

This section covers two ways to analyze if a fit is good.

- Plotting the residuals.

- Doing a \(\chi^2\) test.

4.6.1 Plotting the fit residuals

The first step is to look at the residuals. The residuals, \(r_i\), are defined as the difference between the data and the fit.

\[r_i=y_i-y(x_i,a,b,c, \ ... \ )\]

Make a plot of the residuals:

# Calculate and plot residuals residuals = y_data - beam_profile(x_data, *popt) plt.figure(figsize=(10, 4)) plt.scatter(x_data, residuals) plt.axhline(y=0, color='r', linestyle='--') plt.xlabel('Position (m)') plt.ylabel('Residuals (V)') plt.title('Fit Residuals') plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3) plt.show()Since we didn’t provide any estimates of the uncertainties, the fitting assumed the uncertainty of every point is the same. Based on the plot of residuals, was this a good assumption?

Do the residuals look randomly scattered about zero or do you notice any systematic error sources?

Is the distribution of residuals scattered evenly around zero? Or is there a particular range of \(x\) values where the residuals are larger than others?

What is the most likely source of the large uncertainty as the beam is cut near the center of the beam?

4.6.2 “Chi by eye” - eyeballing the goodness of fit

Question: If I have a good fit, should every data point lie within an error bar?

Answer: No. Most should, but we wouldn’t expect every data point to lie within an error bar. If the uncertainty is Gaussian distributed with a standard deviation \(\sigma_i\) for each data point, \(y_i\), then we expect roughly 68% of the data points to lie within their error bar. This is because 68% of the probability in a Gaussian distribution lies within one standard deviation of the mean.

4.6.3 \(\chi^2\) and \(\chi_{red}^2\) for testing the “goodness” of fit

This section answers the question “What should \(\chi^2\) be for a good fit?”

Suppose the only uncertainty in the data is statistical error, with a known standard deviation \(\sigma_i\), then on average each term in the sum is

\[\frac{1}{\sigma_i^2}(y_i-y(x_i,a,b,c, \ ... \ ))^2 \approx 1\text{,}\](4)

and the full \(\chi^2\) sum of squares is approximately

\[\chi^2 = {\displaystyle \sum_{i=1}^{N}}\frac{1}{\sigma_i^2}(y_i-y(x_i,a,b,c, \ ... \ ))^2\approx N-n\text{.}\quad\quad\](5)

So a good fit has

\[\chi_{red}^2 \equiv \frac{\chi^2}{N-n}\approx 1\text{.}\](6)

- Fact: To find the goodness of fit test, you must first estimate the uncertainties on the data points that you are fitting. How would you explain the reason for this in your own words?

4.6.4 Choosing a strategy to estimate the uncertainty

Considering your answers from Section 4.6.1 (especially 4.6.1.5), which method would give you the best estimate of the uncertainty for each data point, and why?

Eyeballing the fluctuations in each data point.

Taking \(N\) measurements at each razor position and then going to the next position.

Taking the entire data set \(N\) times.

4.6.5 Weighted fits

When you have estimated the uncertainty \(\sigma_i\) of each data point \(y_i\) you should use this information when fitting to correctly evaluate the \(\chi^2\) expression in Equation 1. The points with high uncertainty contribute less information when choosing the best fit parameters.

In Python’s curve_fit, you provide

uncertainties using the sigma parameter:

# Weighted fit with known uncertainties

popt, pcov = curve_fit(

beam_profile,

x_data,

y_data,

p0=p0,

sigma=sigma_list, # Your uncertainty estimates

absolute_sigma=True # Use actual sigma values (not relative)

)Download this data set for a beam size measurement with uncertainties. The first column is razor position in meters, the second column is photodetector output voltage, and the third column is the uncertainty on the photodetector output voltage.

# Load data with uncertainties data = np.loadtxt('profile_data_with_errors.csv', delimiter=',', skiprows=1) x_data = data[:, 0] y_data = data[:, 1] y_err = data[:, 2]Do a weighted fit using the same fit function as in Section 4.3. Use the uncertainty estimates in the third column.

# Weighted fit popt, pcov = curve_fit( beam_profile, x_data, y_data, p0=[1.4, 0.01, 0.0005, 1.45], sigma=y_err, absolute_sigma=True ) perr = np.sqrt(np.diag(pcov))Calculate \(\chi^2\):

# Calculate chi-squared y_fit = beam_profile(x_data, *popt) chi2 = np.sum(((y_data - y_fit) / y_err)**2) dof = len(y_data) - len(popt) # degrees of freedom chi2_red = chi2 / dof print(f"Chi-squared: {chi2:.2f}") print(f"Degrees of freedom: {dof}") print(f"Reduced chi-squared: {chi2_red:.2f}")How close is the reduced chi-squared to 1?

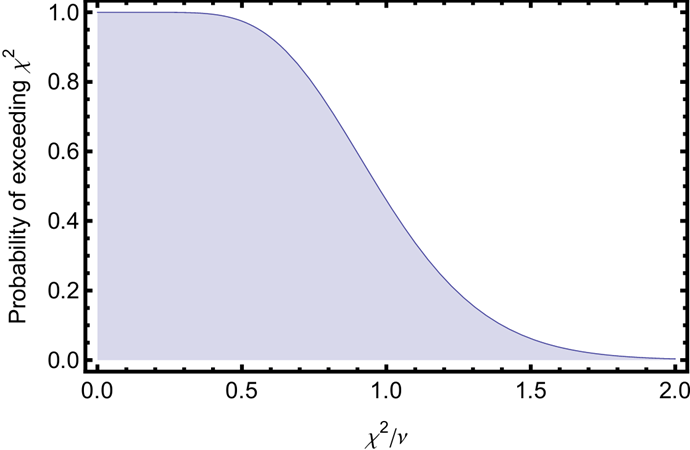

The “chi-squared test”. This part helps us understand if the value of \(\chi^2\) is statistically likely or not. The following graph gives the probability of exceeding a particular value of \(\chi^2\) for \(\nu=𝑁−𝑛=22\) degrees of freedom. It can be calculated using the Cumulative Density Function (CDF) for the chi-squared distribution. Use the graph to estimate the likelihood this value of \(\chi^2\) occurred by chance.

from scipy import stats # Calculate p-value (probability of getting this chi2 or higher by chance) p_value = 1 - stats.chi2.cdf(chi2, dof) print(f"P-value: {p_value:.4f}")

4.6.6 Why is it often bad to overestimate uncertainties?

- Why can overestimating the uncertainty make your fit appear good (i.e., \(\frac{\chi^2}{N-n}\approx 1\))?

Overestimating the uncertainties makes the fit seem good (according to a \(\chi^2\) test), even when it might be obviously a bad fit. It is best to do the \(\chi^2\) test using an honest estimate of your uncertainties. If the \(\chi^2\) is larger than expected \((\chi^2>𝑁−𝑛)\), then you should consider both the possibility of systematic error sources and the quality of your estimates of the uncertainties. On the other hand, if the \(\chi^2\) test is good \((\chi^2\approx 𝑁−𝑛)\), then it shows you have a good handle on the model of your system, and your sources of uncertainty. Finally, if \(\chi^2\ll (𝑁−𝑛)\), this likely indicates overestimated uncertainties.

4.6.7 When does

curve_fit underestimate the true uncertainty?

The uncertainty reported by curve_fit comes

from the covariance matrix and assumes:

- The only source of error is statistical noise in your voltage measurements

- This noise is independent for each data point

- Your model perfectly describes the underlying physics

In real experiments, these assumptions often fail. Consider these scenarios relevant to your beam size measurements:

Systematic errors in position: - If your

micrometer has a 0.01 mm systematic offset, this affects all

measurements the same way - curve_fit doesn’t know

about this, so it can’t include it in the parameter uncertainty

- The true uncertainty in beam size includes uncertainty in

position calibration

Model limitations: - The error function model assumes a perfectly Gaussian beam - Real laser beams may have slight deviations from Gaussian - The fit uncertainty assumes the model is exact

Correlated noise: - If 60 Hz interference

affects multiple adjacent points similarly, they’re not

independent - curve_fit assumes independent

errors, so it underestimates uncertainty

Reflection questions:

Under what conditions might the

curve_fituncertainty be a good estimate of your true measurement uncertainty?In Week 4, you’ll extract beam waist \(w_0\) from fits at multiple positions. Besides statistical noise in voltage measurements, what other sources of uncertainty should you consider? List at least two.

4.6.8 Statistical vs. Systematic Uncertainties

Understanding the distinction between statistical and systematic uncertainties is crucial for proper error analysis. This distinction becomes especially important in Week 4 when you construct an uncertainty budget.

Statistical uncertainties (also called “random uncertainties”) are unpredictable fluctuations that vary from measurement to measurement. They average out over many measurements—take 100 readings and compute the mean, and the statistical uncertainty in that mean decreases by \(\sqrt{100} = 10\).

Examples from this lab: - Voltage noise on the photodetector (varies each reading) - Thermal fluctuations in electronic components - Shot noise from photon arrival times

Systematic uncertainties are consistent biases that affect all measurements the same way. They do NOT average out—take 100 readings and the systematic error remains exactly the same.

Examples from this lab: - Micrometer calibration offset (if it reads 0.02 mm high, ALL positions are 0.02 mm high) - DAQ voltage offset (shifts all readings by a fixed amount) - Beam not perfectly perpendicular to knife edge (consistent underestimate of width)

Why this matters for fitting:

curve_fit only sees statistical scatter around

your fit function. It has no way to detect systematic offsets.

If your micrometer is miscalibrated by 0.1 mm, the fit will

find parameters that are systematically shifted, and

curve_fit will not include this in the reported

uncertainty.

Quick self-test: Classify each of these as statistical (St) or systematic (Sy):

- The photodetector gain knob is actually at 28 dB when the label says 30 dB: _____

- 60 Hz pickup causing voltage fluctuations: _____

- The laser power slowly drifting over 30 minutes: _____ (tricky—think about whether it averages out)

- Room lights flickering: _____

Answers: 1=Sy, 2=St (if averaging over many cycles), 3=Sy (drift is correlated, doesn’t average out), 4=St

In Week 4, when you construct your uncertainty budget, you will need to identify the dominant sources of both statistical AND systematic uncertainty, and combine them appropriately.

4.7 Error bars

The error bar is a graphical way to display the uncertainty in a measurement. In order to put error bars on a plot you must first estimate the error for each point. Anytime you include error bars in a plot you should explain how the uncertainty in each point was estimated (e.g., you “eyeballed” the uncertainty, or you sampled it \(N\) times and took the standard deviation of the mean, etc.)

4.7.1 Error bars in Python with Matplotlib

Creating plots with error bars in Python is straightforward

using plt.errorbar():

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Load data with uncertainties

data = np.loadtxt('gaussian_data_with_errors.txt', skiprows=1)

x = data[:, 0] # Position

y = data[:, 1] # Voltage

y_err = data[:, 2] # Uncertainty

# Create plot with error bars

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.errorbar(x, y, yerr=y_err, fmt='o', capsize=3,

label='Data with uncertainties')

plt.xlabel('Micrometer Position (inches)')

plt.ylabel('Photodetector Voltage (V)')

plt.title('Gaussian Beam Size Measurement')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.show()The errorbar() function parameters: -

x, y: Data points -

yerr: Uncertainty values (can also use

xerr for horizontal error bars) -

fmt='o': Marker style (circles) -

capsize=3: Size of error bar caps

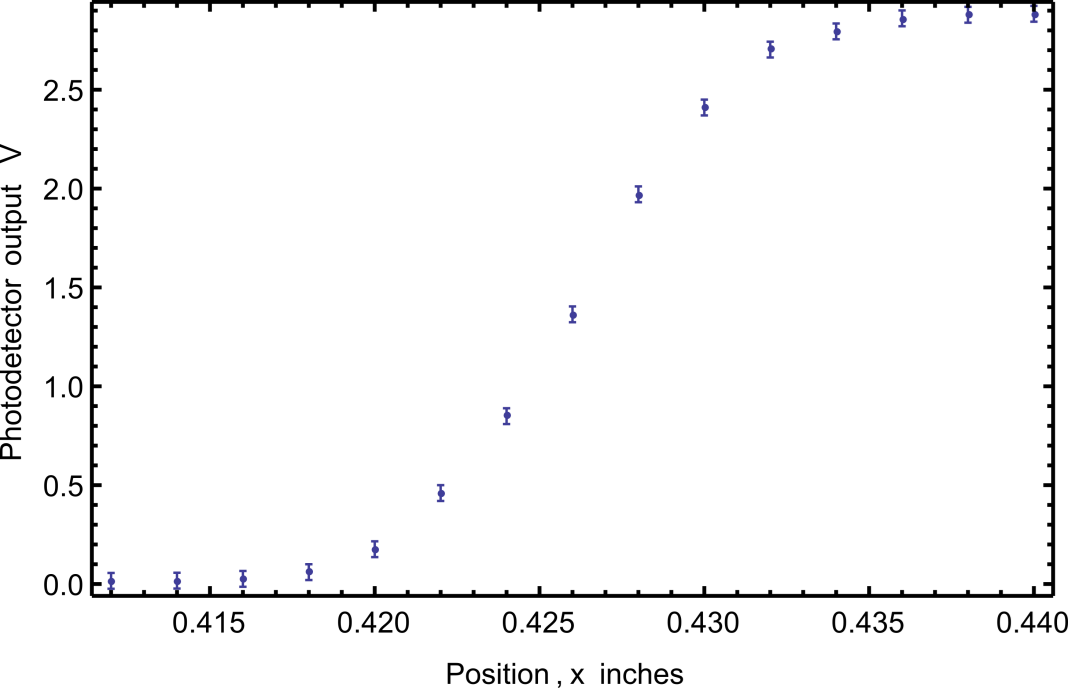

4.7.2 Example: Gaussian laser beam size measurement

Suppose you had estimated the uncertainty at every point in a width measurement of your Gaussian laser beam to be \(0.04 \ V\). This error was chosen to demonstrate the mechanics of making a plot with error bars, but the uncertainty in the actual data was probably smaller than this.

| Micrometer Position (inches) | Photodetector Voltage (V) | Estimated uncertainty (V) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.410 | 0.015 | 0.04 |

| 0.412 | 0.016 | 0.04 |

| 0.414 | 0.017 | 0.04 |

| 0.416 | 0.026 | 0.04 |

| 0.418 | 0.060 | 0.04 |

| 0.420 | 0.176 | 0.04 |

| 0.422 | 0.460 | 0.04 |

| 0.424 | 0.849 | 0.04 |

| 0.426 | 1.364 | 0.04 |

| 0.428 | 1.971 | 0.04 |

| 0.430 | 2.410 | 0.04 |

| 0.432 | 2.703 | 0.04 |

| 0.434 | 2.795 | 0.04 |

| 0.436 | 2.861 | 0.04 |

| 0.438 | 2.879 | 0.04 |

| 0.440 | 2.884 | 0.04 |

Download this data set and create a plot with error bars like Figure 3.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Load data

data = np.loadtxt('gaussian_data_with_errors.txt', skiprows=1)

position = data[:, 0]

voltage = data[:, 1]

uncertainty = data[:, 2]

# Create plot

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.errorbar(position, voltage, yerr=uncertainty,

fmt='o', capsize=3, markersize=5)

plt.xlabel('Position (inches)')

plt.ylabel('Photodetector Output (V)')

plt.title('Gaussian Beam Size Measurement')

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

4.8 Prelab Exercise: Error Function Fitting Practice

Now that you understand curve fitting, apply it to beam size analysis. This exercise prepares you for analyzing your own knife-edge measurements.

Note on AI assistance: You may use AI tools

to help write your curve fitting code. However, the learning

goal is to understand what the code does and why. Be prepared

to explain: (1) what the fit parameters mean physically, (2)

why the error function is the appropriate model, and (3) how to

interpret the uncertainties reported by

curve_fit.

4.8.1 The Error Function Model

In Week 1, you derived that blocking a Gaussian beam with a knife edge produces a signal described by:

\[P(x) = \frac{P_0}{2}\left[1 + \text{erf}\left(\frac{\sqrt{2}(x-x_0)}{w}\right)\right]\]

where \(w\) is the beam radius, \(x_0\) is the beam center position, and \(P_0\) is the total power.

For fitting, we use a slightly more general form that accounts for offsets:

\[y(x) = a \cdot \text{erf}\left(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{w}(x-b)\right) + c\]

where: - \(a\) = amplitude (half the voltage swing) - \(b\) = beam center position - \(w\) = beam radius (what we want!) - \(c\) = vertical offset

Note on terminology: The parameter \(w\) is the beam radius—specifically, the \(1/e^2\) radius where intensity drops to \(1/e^2\) of the peak value. This is not the beam diameter (which would be \(2w\)) or the FWHM. Gaussian beam parameters are discussed further in Week 3.

4.8.2 Practice Exercise

Download Test_Profile_Data.csv and complete the following:

Plot the raw data (position vs. voltage). Does it look like an error function?

Define the fit function (same as used earlier):

from scipy.special import erf def beam_profile(x, amplitude, center, width, offset): """Error function model for knife-edge beam profile. Parameters: x: position (m) amplitude: half the voltage swing (V) center: beam center position (m) width: beam radius w (m) offset: vertical offset (V) """ return amplitude * erf(np.sqrt(2) * (x - center) / width) + offsetPerform the fit:

from scipy.optimize import curve_fit # Load data data = np.loadtxt('Test_Profile_Data.csv', delimiter=',', skiprows=1) x = data[:, 0] # Position (m) y = data[:, 1] # Voltage (V) # Initial guesses (estimate from your plot) # Order: [amplitude, center, width, offset] p0 = [1.0, 0.001, 0.0005, 0.5] # Fit popt, pcov = curve_fit(beam_profile, x, y, p0=p0) perr = np.sqrt(np.diag(pcov)) # Standard errors print(f"Beam size w = {popt[2]:.2e} ± {perr[2]:.2e} m")Verify your result: You should get \(w = 4.52 \times 10^{-4}\) m (approximately 0.45 mm).

Plot data and fit together to verify the fit is reasonable.

Interpret the uncertainties: What is the fractional uncertainty in your beam size? Is this uncertainty dominated by statistical noise or could there be systematic effects?

Save your fitting code—you will use this same procedure to analyze your own knife-edge data in lab.

5 Introduction to Python for Data Acquisition

In this part of the lab, you will learn to use Python for

data acquisition. We’ll use the nidaqmx library to

interface with National Instruments DAQ devices.

5.1 Development Environment

For this lab, we recommend starting with Jupyter Notebook for interactive exploration, then transitioning to VS Code or another editor for writing reusable scripts. See the Python Resources page for setup instructions.

5.2 Connect the USB-6009 and verify it is working

Ensure the NI-DAQmx drivers are installed (they should already be on lab computers). If needed, download from NI-DAQmx.

Connect the USB cable to your computer and the USB-6009.

Open NI Measurement & Automation Explorer (NI-MAX) to verify the device is recognized:

- The device should appear under “Devices and Interfaces”

- Right-click and run “Self-Test” to verify the connection

- Open the “Test Panel” to test analog inputs manually

Use Python to list available DAQ devices:

import nidaqmx from nidaqmx.system import System # List all connected DAQ devices system = System.local() for device in system.devices: print(f"Device: {device.name}") print(f" Product Type: {device.product_type}") print(f" AI Channels: {[ch.name for ch in device.ai_physical_chans]}")Connect the 5V power rail to

AI0+and ground toAI0-. You must connect both wires since the device measures a potential difference between the two terminals.Read a voltage to verify the connection:

with nidaqmx.Task() as task: task.ai_channels.add_ai_voltage_chan("Dev1/ai0") voltage = task.read() print(f"Measured voltage: {voltage:.4f} V")

5.3 Reading Multiple Samples

To capture time-varying signals, you need to configure the sample rate and number of samples.

5.3.1 Understanding Sample Rate and Samples to Read

When acquiring data, you must specify:

- Sample Rate: How many samples per second (Hz)

- Samples to Read: Total number of samples to acquire

For example, to capture 5 periods of a 1 kHz sine wave with 20 samples per period:

- Samples to Read = 5 periods × 20 samples/period = 100 samples

- Total time = 5 periods / 1000 Hz = 5 ms

- Sample Rate = 100 samples / 0.005 s = 20,000 Hz

5.3.2 Acquiring Multiple Samples

import nidaqmx

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from nidaqmx.constants import AcquisitionType

# Configuration

sample_rate = 20000 # Hz

samples_to_read = 100

# Acquire data

with nidaqmx.Task() as task:

task.ai_channels.add_ai_voltage_chan("Dev1/ai0")

task.timing.cfg_samp_clk_timing(

rate=sample_rate,

sample_mode=AcquisitionType.FINITE,

samps_per_chan=samples_to_read

)

data = task.read(number_of_samples_per_channel=samples_to_read)

# Create time array

time = np.arange(samples_to_read) / sample_rate

# Plot the data

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(time * 1000, data) # Time in ms

plt.xlabel('Time (ms)')

plt.ylabel('Voltage (V)')

plt.title('Acquired Signal')

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.show()5.3.3 Exercise: Capture a Waveform

Equipment: Use the Tektronix TBS 2000 Series oscilloscope and Keysight EDU33212A waveform generator at your station. These are the same instruments you used in PHYS 3330.

- Connect your waveform generator to both an oscilloscope and your DAQ device.

- Set the waveform generator to output a sine wave at a frequency compatible with your sample rate calculation.

- Modify the sample rate and samples to read to capture approximately 5 complete periods.

- Run the acquisition and compare the Python plot with the oscilloscope display. Are they compatible?

- Add to your notebook: the Python code, the resulting plot, and the oscilloscope output. Explain how they all make sense together.

6 Digital Sampling and Nyquist Frequency

Now that you can acquire data with the DAQ, it’s important to understand how the choice of sample rate affects your measurements. This section explores what happens when you sample a signal too slowly.

6.1 Exploring Sample Rate Effects

Modify your Python script so that the Number of Samples and Sample Rate are easily configurable variables at the top:

import nidaqmx import numpy as np import matplotlib.pyplot as plt from nidaqmx.constants import AcquisitionType # Configuration - easily adjustable SAMPLE_RATE = 500 # Samples per second NUM_SAMPLES = 500 # Total samples (1 second of data) DAQ_CHANNEL = "Dev1/ai0" def acquire_data(sample_rate, num_samples, channel): """Acquire data from DAQ with specified parameters.""" with nidaqmx.Task() as task: task.ai_channels.add_ai_voltage_chan(channel) task.timing.cfg_samp_clk_timing( rate=sample_rate, sample_mode=AcquisitionType.FINITE, samps_per_chan=num_samples ) data = task.read(number_of_samples_per_channel=num_samples) return np.array(data)Set up a function generator to produce a 1 kHz sine wave.

Connect the function generator’s output to both the oscilloscope and the DAQ.

6.2 Initial Measurements

Set the sample rate in your Python script to 500 samples per second and the number of samples such that it records 1 second of data.

Record and plot a dataset with both the oscilloscope and the DAQ. Make sure that the time range on the oscilloscope is set such that it is on the same order as the data being recorded by the DAQ.

# Acquire and plot data data = acquire_data(SAMPLE_RATE, NUM_SAMPLES, DAQ_CHANNEL) time = np.arange(NUM_SAMPLES) / SAMPLE_RATE plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6)) plt.plot(time, data) plt.xlabel('Time (s)') plt.ylabel('Voltage (V)') plt.title(f'Acquired Signal ({SAMPLE_RATE} Hz sample rate)') plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3) plt.show()Compare the two plots. What are the major differences between the two?

Why might one or both of these plots be giving an incorrect result? Think about the wave you are measuring and the result you are getting. How do they relate?

6.3 Enhanced Understanding

This section will guide you to an understanding of Nyquist’s theorem and a more appropriate sample rate for digital data collection.

Why do you think the data from the DAQ produced a wave of lower frequency?

Adjust the sample rate in a way you think might provide a more accurate measurement of the wave. What do you think the measured waveform will look like this time?

Take a dataset, record and plot it. Did it match your predictions?

Now record another dataset with the function generator set to the same parameters but the sample rate set to 3000 samples per second and the number of samples set to record 1 second of data.

Plot this new dataset. What is the frequency of the new dataset?

What are the fundamental differences between the first, second, and third datasets?

6.4 Nyquist Frequency

The discrepancies between the sampled waveforms can be explained by Nyquist’s theorem. It states that to accurately measure a signal by discrete sampling methods (like the DAQ) the sampling rate must be at least twice that of the measured signal. If this were not the case, a measurement might not be taken at every interval of oscillation, a situation called “undersampling.” Sampling the signal at least twice as fast as the maximum frequency of interest ensures that at least two data points are recorded each period.

Definition:

The Nyquist Frequency is defined to be half the sample rate.

6.4.1 Aliasing Exercises

Predict the apparent frequency (in Hz) of the signal recorded by the DAQ. Observe what really happens using your waveform generator, DAQ, and Python script. Explain the result. Suppose the DAQ is set to 1 kS/s sample rate in all of the cases, while the waveform generator is set to:

- 1000 Hz

- 998 Hz

- 1004 Hz

- 1500 Hz

- 2000 Hz

- 1997 Hz

- 2005 Hz

In understanding what is going on, it may help to draw a few periods of the wave and then indicate where the DAQ will sample the waveform.

You want to measure the random fluctuations (noise) in a signal from 0-100 Hz.

- If you set the sample rate at 200 Hz, what set of frequency ranges will contribute to the noise measurement?

- If you set the sample rate at 1000 Hz, what set of frequency ranges will contribute to the noise measurement?

- How could you help achieve the desired measurement in 2.1 using a combination of changing the sample rate and adding filtering? Explain why your choice of sample rate and signal filter would work better.

Undersampling on the oscilloscope. Undersampling is an issue with any device that samples data at regular discrete time intervals. This question requires the use of a Tektronix TBS 2000 Series oscilloscope and the Keysight EDU33212A waveform generator.

- The oscilloscope’s sample rate depends on the time/div setting. On the Tektronix TBS 2000, you can see acquisition information by pressing Acquire on the front panel. The sample rate changes as you adjust the horizontal (time) scale—slower time scales use lower sample rates.

- Predict what you should observe if you set the waveform generator to the same frequency as the oscilloscope’s sample rate. Try it out, compare with your prediction, and explain your observations.

- What happens if you change the oscilloscope time scale? Or change the waveform generator frequency slightly? Try to explain what you observe.

Note: You may need to use the waveform generator’s “Sync/Trigger out” connector to trigger the oscilloscope externally for stable display at certain frequencies.

7 Noise Floor Characterization

You’ve learned how sample rate affects what you can measure—too slow, and you get aliasing. Now you’ll investigate what limits how precisely you can measure: the noise floor.

In Week 1, you calibrated your photodetector’s gain and offset. This week, you’ll characterize your measurement system’s noise floor—and discover what actually limits your measurements.

Connection to Week 1: The “RMS noise” you measure here IS the standard deviation of repeated voltage measurements. When we say the DAQ has “5 mV RMS noise,” we mean that if you sample a constant input many times, the standard deviation will be about 5 mV. This becomes the minimum achievable uncertainty (\(\sigma_V\)) for any voltage measurement.

Connection to aliasing: The noise you’ll measure is broadband—it contains all frequencies. This is why your sample rate matters even for noise measurements: higher sample rates capture more of the noise spectrum.

Why this matters: In Week 4, you’ll measure beam profiles where the signal varies over a wide range. Understanding your actual noise floor is essential for making informed measurement decisions.

7.1 Phase 1: Configuration Discovery

You’ll discover how DAQ configuration affects measurements—and what happens when configuration doesn’t match your physical setup.

7.1.1 Setup

- Ensure nothing is connected to the DAQ inputs.

- Short AI0+ to GND. Leave AI0- disconnected.

This is a reasonable setup for a single-ended measurement: one signal wire connected to ground.

7.1.2 Discovery 1: Configuration Must Match Wiring

The USB-6009 can measure voltages in two ways:

- RSE (Referenced Single-Ended): Measures AI0+ relative to system ground

- Differential: Measures the difference between AI0+ and AI0-

Predict: You’ve grounded AI0+ and left AI0- floating. What will happen if you measure in each mode?

- Both modes will read ~0V (grounded input means zero voltage)

- RSE will work correctly; Differential will give unexpected results

- Differential will work correctly; RSE will give unexpected results

Measure:

import nidaqmx

import numpy as np

from nidaqmx.constants import AcquisitionType, TerminalConfiguration

def measure_noise(channel="Dev1/ai0", num_samples=1000, sample_rate=10000,

terminal_config=TerminalConfiguration.RSE,

voltage_range=10.0):

"""Measure noise with specified configuration."""

with nidaqmx.Task() as task:

task.ai_channels.add_ai_voltage_chan(

channel,

terminal_config=terminal_config,

min_val=-voltage_range,

max_val=voltage_range

)

task.timing.cfg_samp_clk_timing(

rate=sample_rate,

sample_mode=AcquisitionType.FINITE,

samps_per_chan=num_samples

)

data = np.array(task.read(number_of_samples_per_channel=num_samples))

return np.mean(data), np.std(data)

# Compare terminal configurations (same ±10V range)

dc_rse, noise_rse = measure_noise(terminal_config=TerminalConfiguration.RSE, voltage_range=10.0)

dc_diff, noise_diff = measure_noise(terminal_config=TerminalConfiguration.DIFF, voltage_range=10.0)

print(f"RSE ±10V: DC = {dc_rse*1000:7.2f} mV, RMS noise = {noise_rse*1000:.2f} mV")

print(f"DIFF ±10V: DC = {dc_diff*1000:7.2f} mV, RMS noise = {noise_diff*1000:.2f} mV")Record your results:

| Configuration | DC (mV) | RMS Noise (mV) |

|---|---|---|

| RSE ±10V | ||

| DIFF ±10V |

What happened?

- RSE mode measures AI0+ relative to ground. Since AI0+ is grounded, you get ~0V with the expected ~5 mV noise.

- Differential mode measures (AI0+) − (AI0−). AI0+ is grounded (0V), but AI0− is floating—picking up electrical noise from the environment. The result is unpredictable: a large, possibly unstable DC offset and high noise.

The lesson: Your software configuration must match your physical wiring. A floating input in differential mode doesn’t give zero—it gives garbage.

7.1.3 Discovery 2: Voltage Range

Now let’s see how voltage range affects noise with a properly configured measurement.

Change your wiring: Connect both AI0+ and AI0- to GND. This creates a valid zero-volt input for differential mode.

Predict: The ±1V range can measure smaller voltages more precisely than ±10V. Will this affect noise?

- No effect—noise is noise

- Lower noise with ±1V range

- Higher noise with ±1V range

Measure:

# Compare voltage ranges (same DIFF terminal config)

dc_10v, noise_10v = measure_noise(terminal_config=TerminalConfiguration.DIFF, voltage_range=10.0)

dc_1v, noise_1v = measure_noise(terminal_config=TerminalConfiguration.DIFF, voltage_range=1.0)

print(f"DIFF ±10V: DC = {dc_10v*1000:7.2f} mV, RMS noise = {noise_10v*1000:.2f} mV")

print(f"DIFF ±1V: DC = {dc_1v*1000:7.2f} mV, RMS noise = {noise_1v*1000:.2f} mV")Record your results:

| Configuration | DC (mV) | RMS Noise (mV) |

|---|---|---|

| DIFF ±10V | ||

| DIFF ±1V |

7.1.4 What You Discovered

Configuration must match wiring: When you configured differential mode but only grounded AI0+, the floating AI0- produced garbage readings. This is a common mistake—your software settings must match your physical circuit.

Range affects noise: Narrower voltage ranges have lower noise floors. The USB-6009 datasheet confirms this:

- RSE ±10V: ~5 mV RMS

- DIFF ±1V: ~0.5 mV RMS

Tradeoffs exist: Lower noise sounds better, but the ±1V range saturates (clips) any signal above 1V. Your Week 4 beam profile will have signals from near-zero to several volts—you need the ±10V range despite its higher noise.

7.1.5 Configuration for This Lab

For the rest of this lab and Week 4, use RSE mode with ±10V range:

- Your photodetector outputs a single-ended signal (one wire referenced to ground)

- Your signals can exceed 1V

- This matches your Week 1 calibration

Use this function for all remaining measurements:

import nidaqmx

import numpy as np

from nidaqmx.constants import AcquisitionType, TerminalConfiguration

def measure_noise(channel="Dev1/ai0", num_samples=1000, sample_rate=10000):

"""Measure DC level and RMS noise. Uses RSE ±10V configuration."""

with nidaqmx.Task() as task:

task.ai_channels.add_ai_voltage_chan(

channel,

terminal_config=TerminalConfiguration.RSE,

min_val=-10.0,

max_val=10.0

)

task.timing.cfg_samp_clk_timing(

rate=sample_rate,

sample_mode=AcquisitionType.FINITE,

samps_per_chan=num_samples

)

data = np.array(task.read(number_of_samples_per_channel=num_samples))

return np.mean(data), np.std(data)7.2 Phase 2: What Limits Your Measurement?

Now the key question: when you connect your photodetector, will the noise change?

7.2.1 Prediction

Before measuring, make a prediction:

Given information:

- Your DAQ noise (RSE ±10V): ~5 mV RMS (you just measured this)

- Photodetector noise (from datasheet):

- 0 dB gain: ~0.3 mV RMS

- 70 dB gain: ~1.1 mV RMS

Your prediction: When you connect the capped photodetector (dark, no light), the measured noise will:

- Increase significantly (photodetector adds substantial noise)

- Increase slightly (by less than 0.5 mV, since noise adds in quadrature)

- Stay approximately the same (~5 mV)

- Decrease (photodetector somehow reduces noise)

Your reasoning (1-2 sentences): _______________________________________________

7.2.2 Measurement

- Connect the photodetector to the DAQ.

- Cap the photodetector to block all light.

- Measure noise at two gain settings:

# Measure at 0 dB gain (set on photodetector)

dc_0db, noise_0db = measure_noise()

print(f"0 dB gain - Noise: {noise_0db*1000:.2f} mV")

# Change photodetector to 70 dB gain, then measure again

dc_70db, noise_70db = measure_noise()

print(f"70 dB gain - Noise: {noise_70db*1000:.2f} mV")Results:

| Gain | Measured Noise | Photodetector Spec | DAQ Noise |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 dB | _______ mV | 0.3 mV | ~5 mV |

| 70 dB | _______ mV | 1.1 mV | ~5 mV |

7.2.3 Confront Your Prediction

Was your prediction correct? Did noise change significantly when you connected the photodetector?

Reflect on your reasoning: If your prediction was correct, what reasoning led you to the right answer? If incorrect, what assumption failed?

What does this tell you? If noise stayed at ~5 mV regardless of gain, which component dominates your system noise?

Why doesn’t photodetector noise show up? The photodetector’s 0.3-1.1 mV noise is real, but it’s smaller than the DAQ’s 5 mV noise floor. You cannot measure something smaller than your instrument’s noise floor.

7.2.4 The Implication for Gain Selection

Here’s the key insight: if noise is fixed at ~5 mV regardless of gain, then increasing gain improves your signal-to-noise ratio.

| Gain | Signal | Noise | SNR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (0 dB) | Small | ~5 mV | Low |

| High (70 dB) | Large | ~5 mV | High |

The strategy: Use the highest gain that doesn’t saturate your signal.

7.3 Phase 3: Gain Selection for Week 4

Choose your photodetector gain setting for Week 4 beam profile measurements.

Constraints:

- DAQ saturates at ±10 V (photodetector max output is also 10 V)

- DAQ noise floor: ~5 mV RMS

- Your Week 1 calibration data (signal vs. gain)

Your task: Select a gain that maximizes SNR without saturating on your brightest measurement.

Selected gain: _______ dB

Justification (include your reasoning about saturation margin and expected SNR): _______________________________________________

Compare with a neighboring group. Different choices can be valid if the reasoning is sound.

7.4 Looking Ahead

The noise floor you measured (~5 mV) will directly affect your Week 4 beam profile uncertainty:

- Today: You characterized the DAQ noise floor that limits your measurements

- Week 3: You’ll learn how measurement uncertainties propagate through calculations

- Week 4: Your DAQ noise determines uncertainty in each data point, which propagates through curve fitting to give uncertainty in beam size

Keep your noise measurement accessible—you’ll need it for Week 3’s error propagation exercises.

7.5 Optional: Oscilloscope Comparison

The oscilloscope has a much lower noise floor than the DAQ. If time permits, compare noise measurements.

Setup: Connect the photodetector output to oscilloscope CH1.

import pyvisa

import numpy as np

rm = pyvisa.ResourceManager()

scope = rm.open_resource("USB0::0x0699::...") # Your scope address

scope.timeout = 10000

# Capture waveform and compute noise (std dev)

scope.write("DATA:SOURCE CH1")

raw = scope.query_binary_values("CURVE?", datatype='b', container=np.array)

v_scale = float(scope.query("WFMPRE:YMULT?"))

v_off = float(scope.query("WFMPRE:YOFF?"))

voltage = (raw - v_off) * v_scale

print(f"RMS noise: {np.std(voltage)*1000:.2f} mV")

scope.close()See VISA Instrument Control for complete oscilloscope examples.

Question: With the oscilloscope’s lower noise floor, can you now see the photodetector noise increase with gain?

8 Saving Data and Additional DAQ Features

8.1 Saving Data to a File

Save your acquired data to a CSV file for later analysis:

import numpy as np

from datetime import datetime

# After acquiring data...

# Create a timestamp for the filename

timestamp = datetime.now().strftime("%Y%m%d_%H%M%S")

filename = f"data_{timestamp}.csv"

# Create time array

time = np.arange(len(data)) / sample_rate

# Save to CSV

np.savetxt(

filename,

np.column_stack([time, data]),

delimiter=',',

header='Time (s), Voltage (V)',

comments=''

)

print(f"Data saved to {filename}")8.1.1 Exercise: Save and Reload Data

Acquire a waveform and save it to a CSV file.

Load the data back and plot it:

# Load data loaded_data = np.loadtxt(filename, delimiter=',', skiprows=1) time_loaded = loaded_data[:, 0] voltage_loaded = loaded_data[:, 1] # Plot plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6)) plt.plot(time_loaded * 1000, voltage_loaded) plt.xlabel('Time (ms)') plt.ylabel('Voltage (V)') plt.title('Loaded Data') plt.show()Verify the loaded data matches your original acquisition.

8.2 Generating an Analog Output

The USB-6009 can also generate analog voltages (though at a limited rate of 150 S/s). Note that the USB-6009’s analog outputs have a range of 0-5V only, so we must specify this range explicitly:

import nidaqmx

# Output a DC voltage

with nidaqmx.Task() as task:

task.ao_channels.add_ao_voltage_chan("Dev1/ao0", min_val=0.0, max_val=5.0)

task.write(2.5, auto_start=True) # Output 2.5 V

print("Outputting 2.5 V on AO0")

input("Press Enter to stop...")8.2.1 Exercise: Test Analog Output

- Configure your DAQ to output a voltage on

AO0. - Connect

AO0toAI0(loopback test). - Write a script that:

- Outputs a voltage on

AO0 - Reads the voltage on

AI0 - Verifies they match

- Outputs a voltage on

8.3 Error Handling

Always include error handling in your data acquisition code:

import nidaqmx

from nidaqmx.errors import DaqError

try:

with nidaqmx.Task() as task:

task.ai_channels.add_ai_voltage_chan("Dev1/ai0")

voltage = task.read()

print(f"Voltage: {voltage:.4f} V")

except DaqError as e:

print(f"DAQ Error: {e}")

print("Check that:")

print(" - The DAQ device is connected")

print(" - The device name is correct (try 'Dev1', 'Dev2', etc.)")

print(" - NI-DAQmx drivers are installed")9 Summary

In this lab, you learned to:

- Connect and verify a USB DAQ device

- Read single and multiple voltage samples

- Configure sample rate and acquisition timing

- Explain Nyquist’s theorem and recognize aliasing

- Choose appropriate sample rates for your signals

- Discover that DAQ configuration (terminal mode, voltage range) affects noise performance

- Characterize the DAQ noise floor and identify it as the dominant noise source

- Reason through why gain improves SNR when noise is fixed

- Make a quantitative decision about optimal gain for Week 4 measurements

- Save data to CSV files

- Generate analog output voltages

- Handle common errors

Key takeaway: You discovered that instrument behavior depends on configuration—default settings are not always what you expect. You also found that the DAQ noise floor (~5 mV in RSE mode) limits your measurements, not the photodetector noise. These authentic discoveries—that understanding your instruments matters—are central to experimental physics.

See the Python

Resources page and the example scripts in the

python/ folder for more detailed examples.

10 Deliverables and Assessment

Your lab notebook should include the following for this week:

10.1 Prelab (complete before lab)

- Least-squares fitting exercises: contour plot of \(\chi^2\), graphical minimization results

- Residuals analysis: plot of residuals, answers to goodness-of-fit questions

- Weighted fit: results using data with uncertainties, \(\chi^2\) test calculation

- Error bars plot: reproduction of the example plot with error bars

10.2 In-Lab Documentation

- DAQ verification: screenshot or plot showing successful voltage reading

- Waveform capture: comparison of Python plot vs. oscilloscope display

- Aliasing exercises: completed prediction-observation-explanation for all frequency cases

- Configuration discovery (Phase 1):

- DAQ noise with default settings: _______ mV

- DAQ noise with explicit RSE ±10V: _______ mV

- Explanation of why configuration affects noise

- Noise source identification (Phase 2):

- Prediction of whether photodetector changes noise

- Measurements at 0 dB and 70 dB gain

- Conclusion about dominant noise source

- Gain setting decision (Phase 3): your selected gain with written justification

- Peer comparison: other group’s gain setting and brief discussion

10.3 Key Data Table

Photodetector Noise Test

| Gain | Measured Noise | Photodetector Spec | DAQ Noise | Dominant Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 dB | _______ mV | 0.3 mV | ~5 mV | _______ |

| 70 dB | _______ mV | 1.1 mV | ~5 mV | _______ |

10.4 Code Deliverables

- Working

measure_noise()function with explicit RSE configuration - Python script for waveform acquisition and plotting

10.5 Reflection Questions

You measured DAQ noise with two different configurations. Why does the choice of terminal mode and voltage range affect the noise level? What lesson does this teach about working with instruments?

Given that the DAQ noise floor is fixed at ~5 mV (in RSE mode), explain in 2-3 sentences why using higher gain improves SNR. What limits how high you can set the gain?

You discovered that differential mode with ±1V range has ~0.5 mV noise—10× lower than RSE mode. Why can’t you use this lower-noise configuration for your Week 4 measurements?